This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

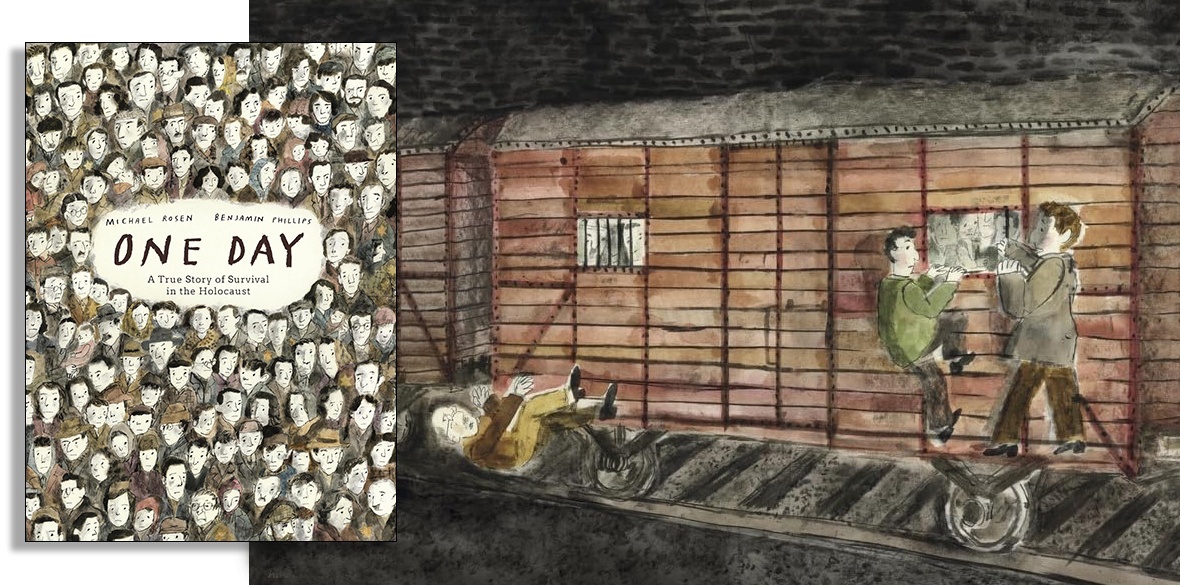

One Day

Michael Rosen & Benjamin Phillips, Walker Studio, £12.99

ARTISTS brave enough to criticise Israel’s catastrophic treatment of the Palestinian people risk a double whammy. Not only do the inevitable allegations of anti-semitism trigger calls for a boycott, but attention shifts from the cultural product to the manufactured scandal.

Consider the cases of musician Roger Waters, film-maker Ken Loach and writer-actor Miriam Margolyes. Then, of course, there’s the children’s writer and poet Michael Rosen.

Rosen has produced several books — fiction, non-fiction and poetry — about the experiences of his Jewish family in World War II. And he has written extensively about the policing of Jewish voices on the Holocaust. There has, he suggests, been a concerted effort to silence those defending Palestinian rights.

His own recent experiences include several cancelled appearances — at a commemoration of the Kindertransport, a Show Racism the Red Card gig and an event for the Anne Frank Trust. He also reports that a key figure in Labour Against Anti-semitism asked the BBC to sack him from Radio 4’s Word of Mouth.

Undeterred by the blocking, brickbats and performative outrage, Rosen has continued to write about the Jewish experience of Nazism.

One Day, a collaboration with the illustrator Benjamin Phillips, is a graphic docufiction for readers aged seven to 10. It tells the story of Jewish Communist Eugene Handschuh, born in Budapest but fighting for the resistance in Paris. Eugene and his father, Oscar, are captured by the French Police in December 1942 and handed to the Nazis. Beaten, starved and subjected to forced labour, they join a group attempting to tunnel out of the Jewish prison camp at Drancy. The failure of this enterprise results in them being scheduled for deportation to Auschwitz in the trucks of Rail Convoy 62.

The rest of the narrative centres on Eugene and Oscar’s escape from the convoy and their return to the Resistance. It’s a tale of bold decisions, outrageous luck and astonishing courage.

The book is age appropriate in terms of tone and image. Both Rosen and Phillips respect the story they are telling and never flinch from its unsettling implications. On the other hand, they do not confront young readers with the overt and relentless horrors portrayed in Art Spiegelman’s Maus.

Phillips’s imagery is unsettling rather than harrowing. It is stark, sombre and conveys the hardships, injuries and despair of the characters. The intricately detailed crowd scenes are rendered in loose, sketchy lines: faces are idiosyncratic and expressive. The style is reminiscent of the illustrations of Edward Ardizzone, but with a more austere palette and a striking relish for the textures of the built environment.

There’s little sense of jeopardy in the plot. We know from the outset that the protagonists live to fight again and tell their stories, because the book is based on interviews with Eugene in later life.

Rosen read about Eugene and Oscar while researching the fate of family members deported on Convoy 62. None of them returned. This is unsurprising given the fact that 1,200 people were transported on that train, 19 of them escaped by jumping and 29 survived their captivity in Auschwitz.

Eugene and Oscar’s escape provides moments of hope and inspiration against a background of chaos and malevolence. For example, there’s a scene in which Oscar is taken in by farmers Monsieur and Madame Medard, who hide him from the Nazis at great personal risk. I challenge any reader, whatever their age, to read it without feeling profoundly moved.

Explaining genocidal persecution to younger readers is challenging. Rosen and Phillips tackle the theme with honesty, sensitivity and clarity. In the context of 18 months of death, destruction and privation in Gaza, this softly spoken exposition of courage and optimism in the face of human brutality is both uplifting and important.